What are wildcards?

Wildcards are special characters that represent any valid alternative character. In the context of c-squares, wildcards can be used to compactly notate a range of raster cells. Let’s say you have the following string of four c-squares defined:

library(csquares)

csq <- as_csquares("1000:1|1000:2|1000:3|1000:4")

print(csq)

#> csquares [1:1] 4 squaresThese are four squares of 5° by 5°. As you can see the first four

digits of each of the four squares are identical. Therefore, these

squares could be notated as "1000:*" where *

is the wildcard symbol. The wildcard thus represent each of the four

posibble values that are allowed at its position. Constructing a

csquares object with as_csquares() results in

an identical object when the either the long format or the compact

notation with wildcard is used.

csqw <- as_csquares("1000:*")

print(csqw)

#> csquares [1:1] 4 squares

identical(csq, csqw)

#> [1] TRUEExpanding wildcards

‘Ceci n’est pas une pipe’

The csquares object does not store wildcards, as it will

use the expanded format with explicit notation, where each raster cell

is included in the character string and is separated by the pipe

"|" character. The function as_csquares()

wraps a call to expand_wildcards() which expands c-square

codes containing wildcards. It will replace the short notation with

wildcard by pipe seperated csquares codes.

expand_wildcards("1000:*") |>

as.character()

#> [1] "1000:1|1000:2|1000:3|1000:4"Matching wild cards

Wildcards can also be used to query spatial data and select specific blocks of raster cells. When used for searching, the wildcard is sometimes represented by the percentage character instead of an asterisk. For this R package it doesn’t matter. Bother characters are interpreted exactly the same.

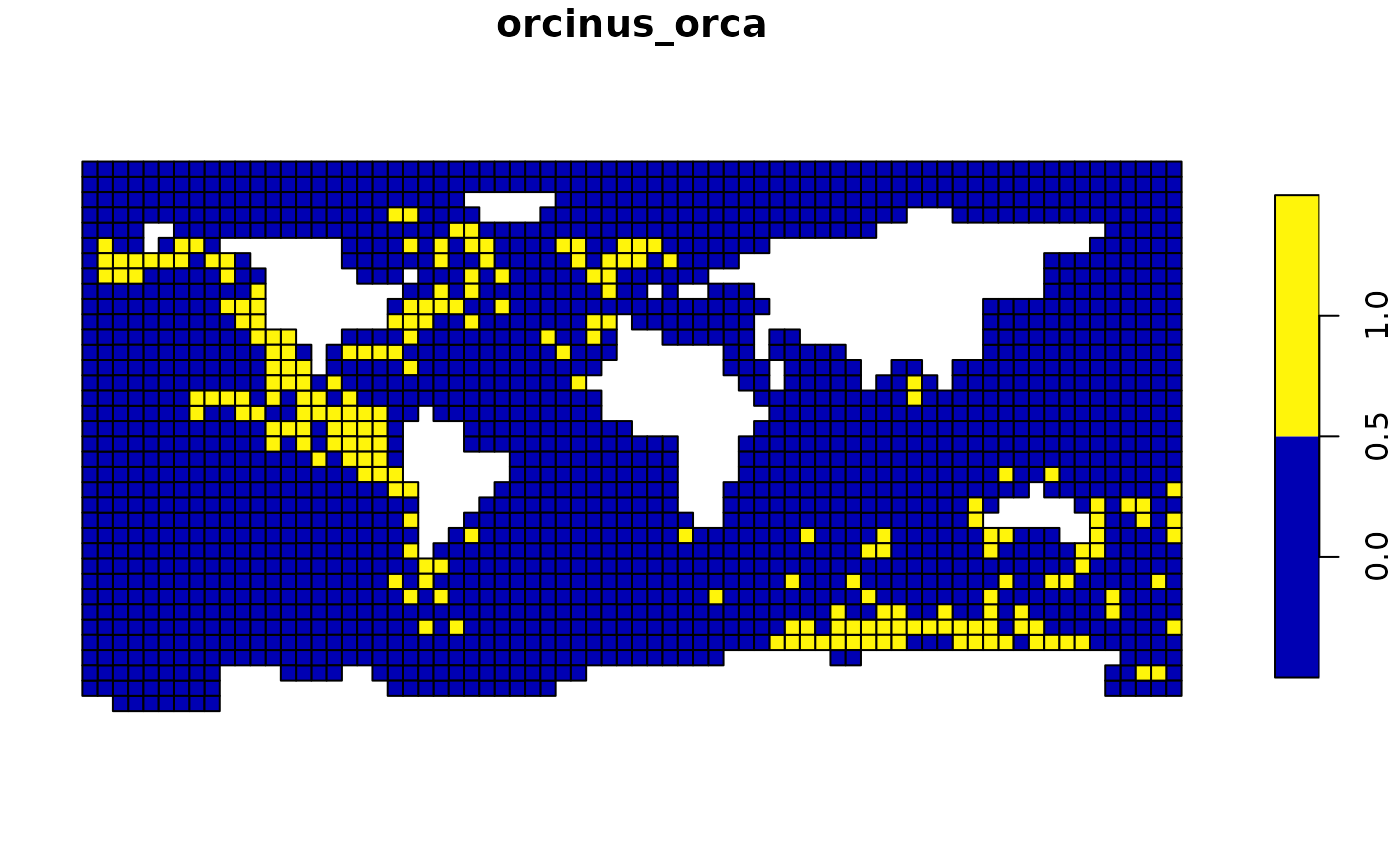

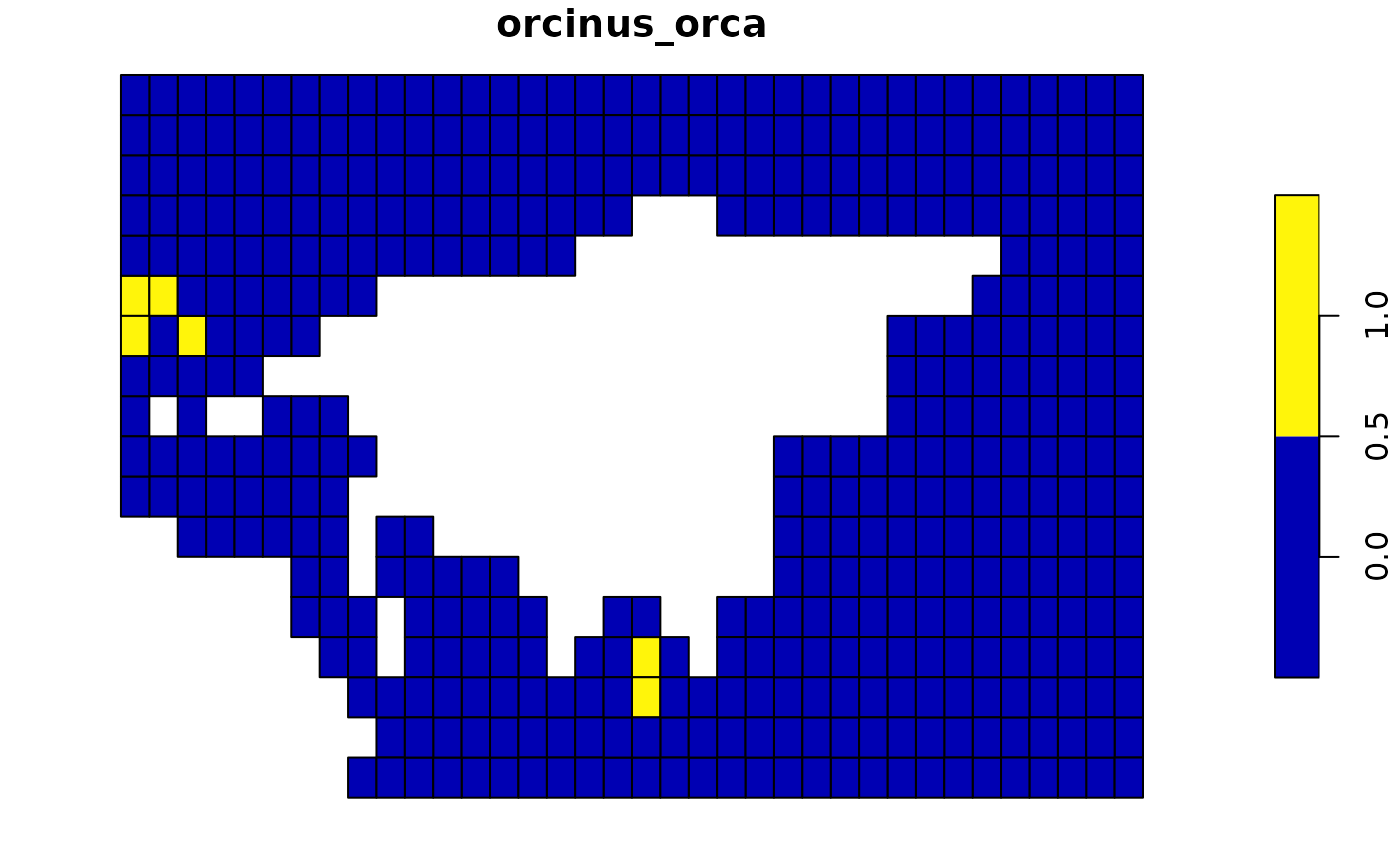

The example below shows how you can filter a specific quadrant from the global killer whale data set using a wildcard notation.

library(dplyr, warn.conflicts = FALSE)

library(sf, warn.conflicts = FALSE)

#> Linking to GEOS 3.12.1, GDAL 3.8.4, PROJ 9.4.0; sf_use_s2() is TRUE

orca_sf <-

orca |>

as_csquares(csquares = "csquares") |>

st_as_sf()

plot(orca_sf["orcinus_orca"])

## Note that the first number in the csquares code (1)

## represents the North East quadrant

## The remainder of the code consists of wildcards.

plot(

orca_sf |>

filter(

in_csquares(csquares, "1***:*")

) |>

drop_csquares() |>

select("orcinus_orca")

)

Mode

Consider the following csquares object:

csq_example <- as_csquares(c("1000:100|1000:111|1000:206|1000:207", "1000:122"))It is a vector of two elements, the first containing 4

squares, the second 1 square. Let’s say we want to check if

"1000:1**" matches with any of the elements in the

vector.

in_csquares(csq_example, "1000:1**")

#> [1] TRUE TRUEWhich is TRUE for both elements in the vector. This

makes sense as both elements indeed contain csquares codes that match

with "1000:1**". However, the first element also contains

elements that don’t match. The reason that the example still returns

TRUE in both cases is because the mode is set

to "any". Meaning that it will return TRUE if

any of the codes in an element matches. You should set the mode to

"all" if you only want a positive match when all codes in

an element match:

in_csquares(csq_example, "1000:1**", mode = "all")

#> [1] FALSE TRUEStrict

Now, let’s compare the same csquares object with

"1000:*" which has a lower resolution than the squares in

the object:

in_csquares(csq_example, "1000:*")

#> [1] TRUE TRUEAgain, it matches with all elements in the vector, even

though the resolution is different. This is because

in_csquares() isn’t very strict by default. Meaning that it

will also match with any ‘child’ square with a higher resolution. If you

want a strict match where the resolution also matches use

strict = TRUE:

in_csquares(csq_example, "1000:*", strict = TRUE)

#> [1] FALSE FALSE